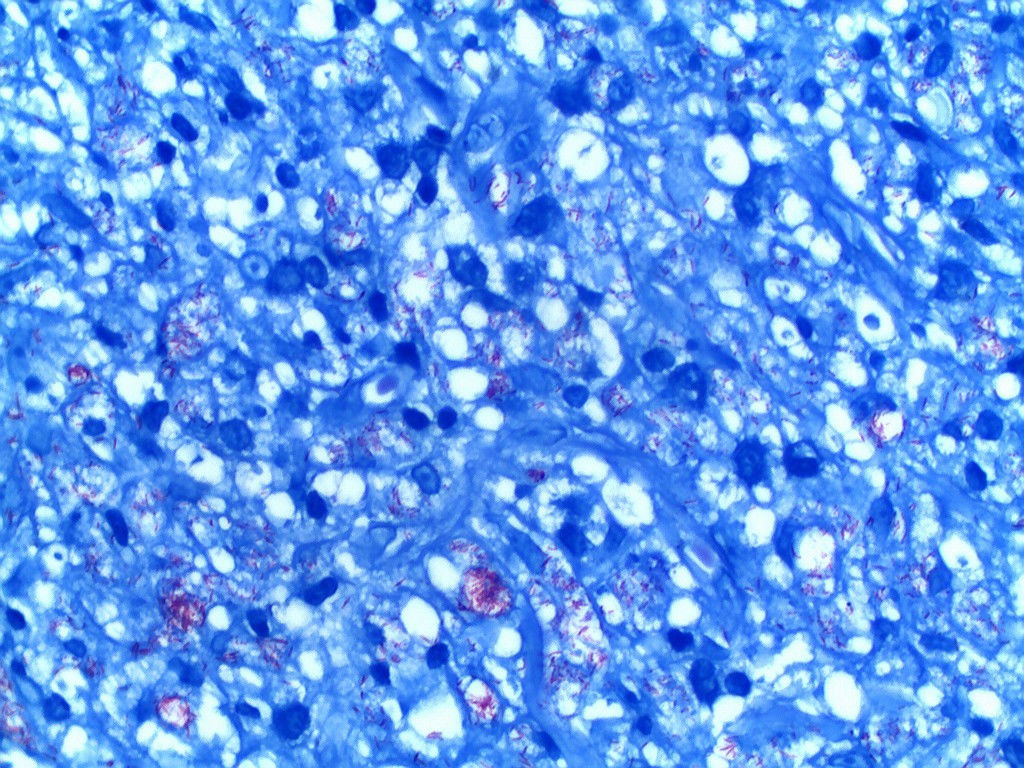

Erythroderma consists of erythema and scaling involving most or all of the body surface. This generalized eruption may be idiopathic, drug-induced or secondary to cutaneous or systemic disease. A 71-year-old man is reported presenting generalized erythema and desquamation with deck-chair sign, nail dystrophy, and plantar ulcers associated with loss of local tactile sensitivity. Biopsies from three different sites demonstrated diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate with incipient granulomas. Fite-Faraco staining showed numerous isolated bacilli and globi. The skin smear was positive. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of borderline lepromatous leprosy was confirmed. This report demonstrates that chronic multibacillary leprosy can manifest as erythroderma and thus should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Leprosy is a chronic contagious infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae with multiple clinical presentations. The specific cellular immune response to the infectious agent is virtually absent in lepromatous leprosy and thus the immune system is unable of eliminating the bacilli, which grow progressively over the years. Multiple peripheral nerves are compromised along the clinical course. Clinical manifestations include ill-defined macules, papules, plaques, and nodules that symmetrically impair extensive areas, along with edema of lower limbs and hypoesthesia of the extremities. Leonine facies and madarosis are commonly reported. Lesions of the borderline lepromatous subgroup resemble those of the lepromatous type: they tend to be numerous, but not necessarily symmetrical, and associate with anesthesic areas. Ichthyosis of the limbs and torso may be a late manifestation in multibacillary patients.1-3

Erythroderma is a clinical syndrome of multiple causes. It is characterized by chronic, persistent, generalized erythema that affects more than 80% or 90% of the body surface, along with scaling for over 15 days. The onset is typically gradual and insidious, except in drug-induced cases that are characterized by abrupt onset and rapid progression. Among the known etiologies, the most common is the aggravation of pre-existing dermatoses, with psoriasis being the most frequent. Other causes include contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus, primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and drug-induced skin disorders.4, 5

Leprosy is not currently considered in the differential diagnosis of exfoliative erythroderma. We report the case of an elderly patient with erythroderma associated with borderline lepromatous leprosy.

Case ReportA 71-year-old male patient presented with erythroderma for approximately 1 year and complained of asthenia and weight loss of 7 kg over a period of 5 years. The patient, who also suffered from hypertension and type-2 diabetes, denied the use of medication and had no personal or family history of of dermatological disorders. He had quit smoking 30 years before.

Physical examination revealed diffuse erythema and desquamation and deck-chair sign, which consists of the conspicuous sparing of the abdominal creases and axillae (Figures 1 and 2). Madarosis, ear nodules, and collapse of the nasal pyramid were absent (Figure 3). Patient presented papules, keratotic plaques, and infiltrates on the nasal, neck, and upper-limb areas. A previous biopsy of all lesions led to the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma. There was no lymph node enlargement. Trophic foot ulcers associated with loss of tactile sensitivity were observed, as well as onychodystrophy of the fingers and toes.

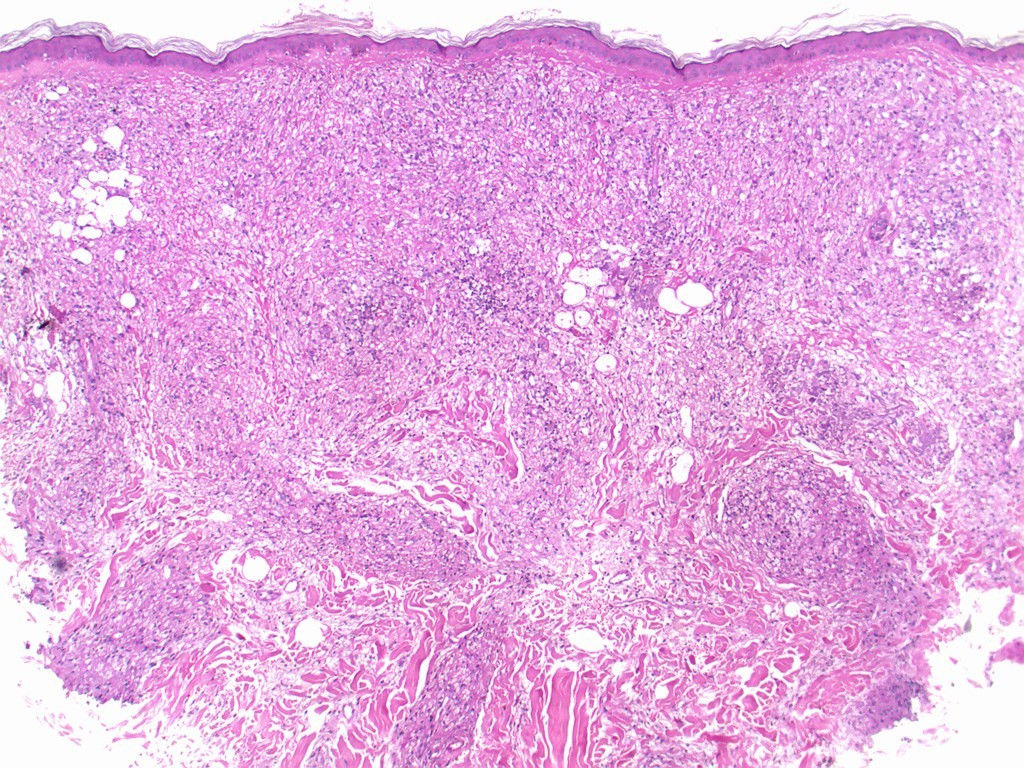

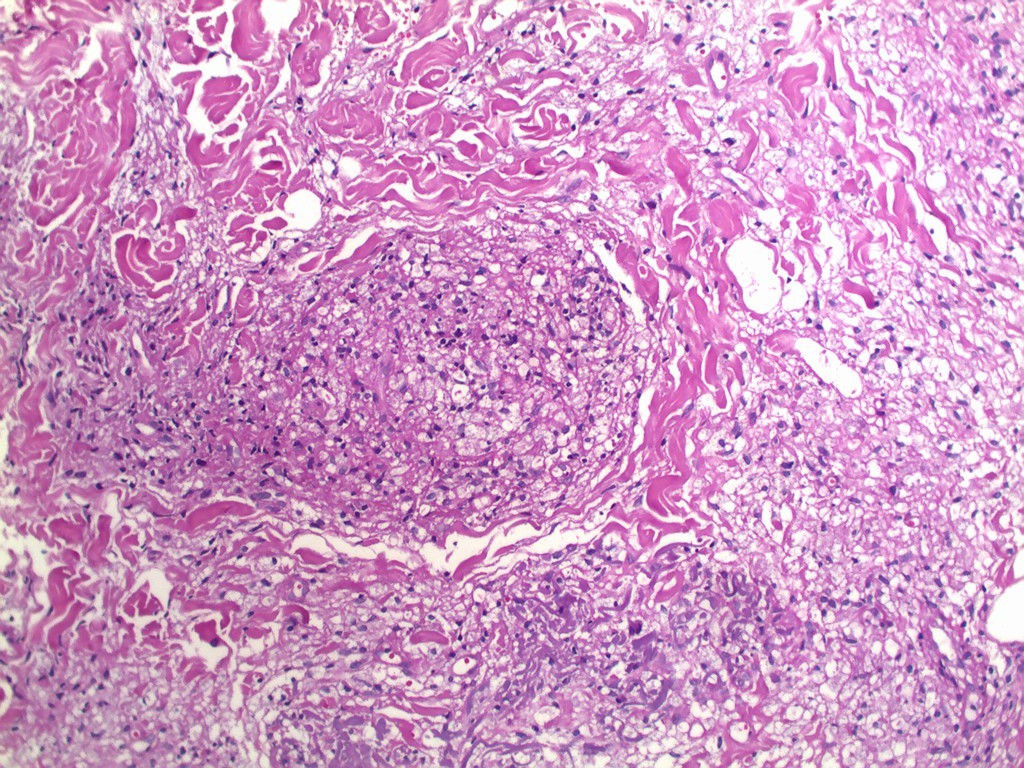

Three biopsy specimen were obtained and histopathological examination showed a generalized mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate containing lymphocytes and numerous histiocytes, with vascular, adnexal, and neural involvement, and few granulomas (Figures 4 and 5). Fite-Faraco staining revealed numerous mycobacteria, some forming globi (Figure 6). Skin smear showed bacilloscopy index 5 according to the Ridley-Jopling scale. Patient was referred to polychemotherapy.

Some of the cases of erythroderma remain idiopathic. Because the specific aspects of the original diseases are typically masked by the unspecific characteristics of erythroderma, it is challenging to properly identify its causes in cases without a previous diagnosis.4

In the case of an elderly patient presenting with weight loss and deck-chair sign, the main hypothesis was cutaneous lymphoma. However, the absence of palpable lymph nodes, loss of distal sensitivity and trophic foot ulcers, in addition to diffuse cutaneous infiltrate sparing hot spots corroborate the hypothesis of leprosy as a differential diagnosis. The diagnosis of leprosy is based on clinical, bacilloscopic and histological evidence.6 These results led to the diagnosis of borderline lepromatous leprosy.

In a clinical and prognostic study on erythroderma, Li & Zheng showed that the predominant findings were, in decreasing order: pruritus, fever, edema, chills, nail changes, weakness, lymphadenopathy, weight loss and islands of normal skin. Most clinical features are unspecific, unrelated to the etiology, and provide little diagnostic evidence – except for the nail changes that have been shown to be predictive of psoriasis. Skin biopsies identified the cause of erythrodema in slightly over half of the cases. The most common causative factors were pre-existing dermatoses, followed by idiopathic causes, drug reactions, and malignancies.5 Erythroderma remains a diagnostic challenge. Identifying its etiology is frequently difficult and additional tests may not be helpful. Multiple biopsies increase diagnostic accuracy but it may be necessary to repeat them at different stages of the disease to confirm the diagnosis. The approach consists of general treatment of signs and symptoms as well as addressing the underlying cause.4, 5, 7

Pal & Haroon have also reported pre-existing dermatoses as the most common cause of erythroderma. Nail changes were observed in 80% of the cases. Islands of normal skin (14.4%) and deck-chair sign (5.5%) were observed in dermatoses not previously reported; both signs were present in our patient.8 Shenoy et al. reported the case of a 55-year-old male with a delayed diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy in which they observed a diffuse pattern in the disease manifestation, equivalent to erythroderma, in addition to the presence of deck-chair sign.6

Li & Zheng found causes of erythroderma that had never, or rarely, been reported such as bullous pemphigoid, hypereosinophilic syndrome, dermatomyositis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.5 Miyashiro et al. reported erythroderma in a 63-year-old male patient with diffuse skin infiltration and delayed diagnosis of reversal reaction in borderline borderline leprosy, suggesting that this form of reaction, if intense and uncontrolled, may culminate in erythroderma.9

An epidemiological study of erythroderma has pointed out that, due to its rarity, detection of new cases is typically delayed and happens when neurological damage is mostly irreversible. This is because leprosy is not considered in the diagnostic approach of dermatitis or peripheral neuropathy. The loss of efficacy of health services in developing countries may result in a increase of the number of cases in the next few decades. In addition, the risk of emergence of rifampicin-resistant strains of M. leprae is to be feared.10 Given the possibility that leprosy can clinically present as erythroderma, we suggest its inclusion in the differential diagnosis of erythrodermic syndrome.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.