Melasma is hypermelanosis that affects photoexposed areas, especially in adult women, with a significant impact on quality of life by affecting visible areas and being recurrent, despite treatments. Its pathophysiology is not yet fully understood, but it results from the interaction between exposure factors (e.g., solar radiation and sex hormones) and genetic predisposition. Several dermal stimuli have been identified in the maintenance of melanogenesis in melasma, including the activity of fibroblasts, endothelium and mast cells, which promote elastonization of collagen, structural damage to the basement membrane, the release of growth factors (e.g., sSCF, bFGF, NGF, HGF) and inflammatory mediators (e.g., ET1, IL1, VEGF, TGFb).1–3

This study aimed to explore differentially exposed proteins in melasma skin when compared to adjacent, unaffected, photoexposed skin.

A cross-sectional study was carried out involving 20 women with facial melasma, without specific treatments for 30 days. Two biopsies were performed (by the same researcher), one at the edge of facial melasma and another on unaffected skin, 2 cm away from the first, as previously standardized.1,3 The mechanical extraction of proteins was performed, followed by their enzymatic digestion and mass spectrometry. The project was approved by the institutional ethics committee (n. 1,411,931).

The samples were analyzed in duplicate in the nanoACQUITY-UPLC system coupled to a Xevo-Q-TOF-G2 mass spectrometer, and the results were processed with the ProteinLynx Global Server 3.03v software. The proteins were identified using the ion-counting algorithm, whose spectral patterns were searched in the Homo sapiens database, in the UniProt catalog (https://www.uniprot.org/).

All identified proteins with >95% similarity were included in the analysis. The intensities of the ion peaks were normalized, scaled and compared between topographies by a Bayesian algorithm (Monte Carlo method), which returns a value of p ≤ 0.05 for down-regulated proteins and ≥0.95 for up-regulated proteins, corrected by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.4

The main outcome of the study was the difference between the intensities of the ionic peaks of the proteins (Melasma: M, Perilesional: P). The effect size was estimated by the ratio of these amounts between topographies (M/P). Proteins with an M/P ratio of ≤0.5 or ≥2.0 were considered in this study.

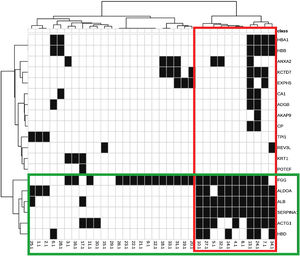

The identified proteins and their biological functions were diagrammed in a heat map and grouped using the cluster procedure (Ward method).

The mean age (standard deviation) of the patients was 42.8 (8.9) years old, 70% were phototypes III‒IV and 25% worked in professions in which they were exposed to the sun. The age of melasma onset was 29.3 (7.5) years; 55% of the women reported a family history and 30% used contraceptives.

A total of 256 proteins were validated in the skin samples, and the 29 proteins differentially quantified between the topographies are shown in Table 1. The greatest discrepancies occurred for proteins HBD, EXPH5, KRT1, KRT9, REV3L (M/S > 4,00); and ACAP9, ADGB, CA1 (M/S < 0.33).

Proteins and isoforms identified in samples of facial melasma (M) and adjacent photoexposed (P) skin (n = 40) with the difference between the groups (p ≤ 0.05 or ≥0.95) and M/P ratio ≥2.0 or ≤0.5.

| Protein code | Protein | PLGS score | Melasma | Perilesional | Log2 M/P (sd) | M/P ratio | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Actin Alpha Skeletal Muscle ACTA1 | 958.81 | 1.34 (0.04) | 0.66 (0.04) | 1.04 (0.07) | 2.05 | 1.00 |

| P2 | Actin Cytoplasmic 2 ACTG1 | 1164.96 | 1.40 (0.06) | 0.60 (0.06) | 1.23 (0.11) | 2.34 | 1.00 |

| Actin Cytoplasmic 2 ACTG1 | 1164.96 | 1.40 (0.07) | 0.60 (0.07) | 1.24 (0.12) | 2.36 | 1.00 | |

| P3 | A-Kinase Anchor Protein 13 AKAP13 | 87.85 | 1.53 (0.40) | 0.47 (0.40) | 1.96 (1.03) | 3.90 | 0.97 |

| A-Kinase Anchor Protein 13 AKAP13 | 87.85 | 1.55 (0.37) | 0.45 (0.37) | 1.99 (1.13) | 3.97 | 0.95 | |

| P4 | A-kinase Anchor protein 9 AKAP9 | 12.43 | 0.35 (0.34) | 1.65 (0.34) | −2.39 (1.00) | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| A-kinase Anchor protein 9 AKAP9 | 13.08 | 0.38 (0.20) | 1.62 (0.20) | −2.16 (0.50) | 0.22 | 0.00 | |

| A-kinase Anchor protein 9 AKAP9 | 16.30 | 0.40 (0.24) | 1.60 (0.24) | −2.06 (0.55) | 0.24 | 0.00 | |

| P5 | Albumin isoform CRA k ALB | 542.99 | 0.62 (0.05) | 1.38 (0.05) | −1.14 (0.08) | 0.45 | 0.00 |

| Serum albumin ALB | 5862.44 | 0.54 (0.18) | 1.46 (0.18) | −1.44 (0.32) | 0.37 | 0.00 | |

| Serum albumin ALB | 542.99 | 0.63 (0.04) | 1.37 (0.04) | −1.14 (0.07) | 0.45 | 0.00 | |

| Serum albumin ALB | 542.99 | 0.52 (0.07) | 1.48 (0.07) | −1.50 (0.12) | 0.35 | 0.00 | |

| Serum albumin ALB | 2923.53 | 0.62 (0.10) | 1.38 (0.10) | −1.17 (0.17) | 0.44 | 0.00 | |

| Serum albumin ALB | 542.99 | 0.63 (0.06) | 1.37 (0.06) | −1.11 (0.10) | 0.46 | 0.00 | |

| Serum albumin ALB | 486.61 | 0.64 (0.06) | 1.36 (0.06) | −1.07 (0.09) | 0.48 | 0.00 | |

| Serum albumin ALB | 534.91 | 0.66 (0.08) | 1.34 (0.08) | −1.04 (0.12) | 0.49 | 0.00 | |

| P6 | Alpha-1-antitrypsin SERPINA1 | 1092.60 | 1.33 (0.13) | 0.67 (0.13) | 1.00 (0.21) | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| P7 | Androglobin ADGB | 69.19 | 0.48 (0.21) | 1.52 (0.21) | −1.69 (0.40) | 0.31 | 0.05 |

| P8 | Annexin ANXA2 | 117.73 | 1.33 (0.25) | 0.67 (0.25) | 1.01 (0.41) | 2.01 | 0.95 |

| Annexin ANXA2 | 117.73 | 1.33 (0.26) | 0.67 (0.26) | 1.02 (0.44) | 2.03 | 0.97 | |

| Annexin ANXA2 | 117.73 | 1.34 (0.26) | 0.66 (0.26) | 1.05 (0.43) | 2.08 | 0.95 | |

| Annexin ANXA2 | 117.73 | 1.35 (0.28) | 0.65 (0.28) | 1.08 (0.43) | 2.12 | 0.95 | |

| P9 | Beta-actin-like protein 2 ACTBL2 | 101.00 | 1.43 (0.07) | 0.57 (0.07) | 1.34 (0.12) | 2.53 | 1.00 |

| P10 | BTB/POZ domain-containing protein KCTD7 | 53.81 | 1.57 (0.17) | 0.43 (0.17) | 1.90 (0.40) | 3.74 | 1.00 |

| P11 | Carbonic Anhydrase 1 CA1 | 1112.39 | 0.39 (0.17) | 1.61 (0.17) | −2.09 (0.45) | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| Carbonic Anhydrase 1 CA1 | 1386.45 | 0.47 (0.13) | 1.53 (0.13) | −1.70 (0.27) | 0.31 | 0.00 | |

| P12 | Ceruloplasmin CP | 76.55 | 1.40 (0.17) | 0.60 (0.17) | 1.23 (0.30) | 2.34 | 1.00 |

| Ceruloplasmin CP | 85.85 | 1.37 (0.17) | 0.63 (0.17) | 1.13 (0.29) | 2.18 | 1.00 | |

| Ceruloplasmin CP | 85.85 | 1.43 (0.15) | 0.57 (0.15) | 1.34 (0.27) | 2.53 | 1.00 | |

| P13 | DNA polymerase zeta catalytic subunit REV3L | 73.85 | 1.58 (0.34) | 0.42 (0.34) | 2.03 (0.86) | 4.10 | 0.95 |

| DNA polymerase zeta catalytic subunit REV3L | 153.25 | 1.52 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.06) | 1.66 (0.12) | 3.16 | 1.00 | |

| P14 | Exophilin-5 EXPH5 | 40.12 | 1.79 (0.12) | 0.21 (0.12) | 3.16 (0.48) | 8.94 | 1.00 |

| P15 | Fibrinogen Gamma chain FGG | 211.06 | 1.33 (0.16) | 0.67 (0.16) | 1.01 (0.25) | 2.01 | 1.00 |

| P16 | Fibrinogen Gamma chain FGG | 211.06 | 1.34 (0.14) | 0.66 (0.14) | 1.04 (0.24) | 2.05 | 1.00 |

| Fructose-bisphosphate Aldolase A ALDOA | 153.06 | 1.46 (0.07) | 0.54 (0.07) | 1.43 (0.14) | 2.69 | 1.00 | |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A ALDOA | 296.85 | 1.45 (0.07) | 0.55 (0.07) | 1.41 (0.13) | 2.66 | 1.00 | |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase ALDOA | 295.30 | 1.46 (0.10) | 0.54 (0.10) | 1.43 (0.17) | 2.69 | 1.00 | |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase ALDOA | 295.30 | 1.47 (0.08) | 0.53 (0.08) | 1.46 (0.14) | 2.75 | 1.00 | |

| P17 | G Patch domain-containing protein 1 GPATCH1 | 95.48 | 1.37 (0.14) | 0.63 (0.14) | 1.13 (0.25) | 2.18 | 1.00 |

| G patch domain-containing protein 1 GPATCH1 | 88.85 | 1.60 (0.28) | 0.40 (0.28) | 2.15 (0.66) | 4.44 | 1.00 | |

| P18 | Heat shock protein 75 kDa mitochondrial TRAP1 | 124.78 | 1.43 (0.13) | 0.57 (0.13) | 1.34 (0.24) | 2.53 | 1.00 |

| P19 | Hemoglobin subunit alpha HBA1 | 8552.23 | 1.57 (0.02) | 0.43 (0.02) | 1.88 (0.04) | 3.67 | 1.00 |

| P20 | Hemoglobin subunit beta HBB | 91.85 | 0.65 (0.05) | 1.35 (0.05) | −1.07 (0.08) | 0.48 | 0.00 |

| P21 | Hemoglobin subunit delta HBD | 42.06 | 1.94 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.02) | 5.05 (0.31) | 33.12 | 1.00 |

| P22 | Keratin type I cytoskeletal 9 KRT9 | 340.12 | 1.61 (0.13) | 0.39 (0.13) | 2.05 (0.27) | 4.14 | 1.00 |

| Keratin type I cytoskeletal 9 KRT9 | 190.36 | 1.60 (0.26) | 0.40 (0.26) | 2.06 (0.62) | 4.18 | 1.00 | |

| P23 | Keratin type II cytoskeletal 1 KRT1 | 55.74 | 1.62 (0.06) | 0.38 (0.06) | 2.08 (0.14) | 4.22 | 1.00 |

| P24 | POTE ankyrin domain family member F POTEF | 101.00 | 1.47 (0.07) | 0.53 (0.07) | 1.49 (0.14) | 2.80 | 1.00 |

| P25 | Putative beta-actin-like protein 3 POTEKP | 101.00 | 1.47 (0.09) | 0.53 (0.09) | 1.47 (0.16) | 2.77 | 1.00 |

| P26 | RNA-binding protein 25 RBM25 | 29.17 | 1.57 (0.12) | 0.43 (0.12) | 1.86 (0.25) | 3.63 | 1.00 |

| P27 | Splicing Regulatory glutamine/Lysine-rich protein 1 SREK1 | 79.89 | 1.41 (0.26) | 0.59 (0.26) | 1.28 (0.48) | 2.44 | 1.00 |

| P28 | Tetratricopeptide repeat protein 37 TTC37 | 443.53 | 1.45 (0.21) | 0.55 (0.21) | 1.44 (0.42) | 2.72 | 1.00 |

| Tetratricopeptide repeat protein 37 TTC37 | 449.05 | 1.46 (0.18) | 0.54 (0.18) | 1.47 (0.36) | 2.77 | 1.00 | |

| P29 | Triosephosphate isomerase TPI1 | 475.34 | 1.39 (0.25) | 0.61 (0.25) | 1.23 (0.41) | 2.34 | 0.97 |

| Triosephosphate isomerase TPI1 | 475.34 | 1.41 (0.22) | 0.59 (0.22) | 1.28 (0.40) | 2.44 | 0.97 | |

| Triosephosphate isomerase TPI1 | 576.90 | 1.43 (0.19) | 0.57 (0.19) | 1.34 (0.37) | 2.53 | 1.00 |

The main biological functions of these proteins are shown in Table 2. Fig. 1 represents the interaction between the 29 proteins and their biological functions. Proteins ACTG1, ALB, SERPINA1, HBD, ALDOA, and FGG showed to be co-participants in different biological processes, such as oxygen consumption, glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and cell transport, suggesting an increase in the metabolic activity of the skin with melasma.

Main functional pathways associated with the 29 proteins identified as differentials between melasma and perilesional skin.

| Functions | Involved proteins | n (%) | FDRa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Canonical glycolysis | p16, p29 | 2 (7) | <0.0001 |

| 2. Gluconeogenesis | p16, p29 | 2 (7) | <0.0001 |

| 3. Fibrinolysis | p8, p15, p23 | 2 (10) | <0.0001 |

| 4. Platelet degranulation | p2, p5, p6, p15, p16 | 5 (17) | <0.0001 |

| 5. Regulation of body fluids | p2, p5, p6, p8, p15, p16, p21, p22, p23 | 8 (28) | <0.0001 |

| 6. Oxygen transport | p7, p19, p20, p21 | 4 (14) | <0.0001 |

| 7. Vesicle-mediated transport | p2, p5, p6, p10, p14, p15, p16, p19, p20 | 9 (31) | <0.0001 |

| 8. Platelet activation | p5, p6, p15, p16 | 4 (14) | <0.0001 |

| 9. Positive regulation of cell adhesion | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0001 |

| 10. Hemostasis | p2, p5, p6, p15, p16, p21 | 6 (20) | 0.0001 |

| 11. Platelet aggregation | p2, p15 | 2 (7) | 0.0002 |

| 12. Plasminogen activation | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0003 |

| 13. Single-organism transport | p2, p5, p6, p7, p8, p10, p11, p12, p14, p15, p16, p19, p20, p21 | 14 (48) | 0.0004 |

| 14. Blood clotting | p2, p5, p6, p15, p16, p21 | 6 (21) | 0.0008 |

| 15. Error-prone translesion synthesis | p13 | 1 (3) | 0.0010 |

| 16. Protein activation cascade | p15, p23 | 2 (7) | 0.0014 |

| 17. Retinal homeostasis | p2, p5, p23, p24 | 4 (14) | 0.0015 |

| 18. Down-regulation of trauma response | p8, p10, p15 | 3 (10) | 0.0015 |

| 19. Up-regulation of exocytosis | p14, p15 | 2 (7) | 0.0016 |

| 20. Regulation of exocytosis | p10, p14, p15 | 3 (10) | 0.0017 |

| 21. Down-regulation of endothelial cell apoptosis process | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0022 |

| 22. Blood clotting, fibrin clot formation | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0024 |

| 23. Down-regulation of the extrinsic apoptosis signaling pathway through the receptor death domain | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0024 |

| 24. Transport | p2, p4, p5, p6, p7, p10, p11, p12, p15, p16, p19, p20, p21 | 13 (45) | 0.0029 |

| 25. Monocarboxylic Acid Metabolic Process | p5, p16, p29 | 3 (10) | 0.0030 |

| 26. Regulation of adhesion-dependent cell spread | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0033 |

| 27. Wound healing | p2, p5, p6, p15, p16, p21 | 6 (20) | 0.0035 |

| 28. Bicarbonate transport | p11, p19, p20 | 3 (10) | 0.0044 |

| 29. Up-regulation of vasoconstriction | p15 | 1 (3) | 0.0044 |

| 30. Response to calcium ion | p2 | 1 (3) | 0.0075 |

| 31. Regulation of transport by vesicles | p8, p10, p14, p15 | 4 (14) | 0.0083 |

| 32. Secretion | p5, p6, p8, p15, p16 | 5 (17) | 0.0092 |

| 33. Down-regulation by external stimuli | p8, p10, p15 | 3 (10) | 0.0098 |

| 34. Response to stress | p2, p5, p6, p13, p16, p19, p20, p21, p23 | 9 (31) | 0.0100 |

Heat map and dendrograms between identified proteins (rows) and biological functions (columns). Green highlights: grouping of proteins with a similar pattern of occurrence according to the functions they perform; and in red: the functions with a similar expression pattern, according to the indicated proteins.

Exophyllin-5 (EXPH5) is linked to intracellular vesicle transport. It was up-regulated (M/S = 8.94) in melasma, which may be due to the intense epidermal transfer of melanosomes.1 Thirteen of the proteins differentially identified in melasma have been linked to intracellular transport phenomena, which comprise a series of processes ranging from endocytosis to autophagy and several forms of exocytosis. As autophagy and senescence are melanogenesis-related phenomena, characterization of transport vesicles in the melasma epithelium may prove to be important in the pathophysiology of melasma.5,6

Cytokeratins (such as KRT1) are structural constituents of keratinocytes induced in response to oxidative stress. They were identified in greater proportion in melasma (M/S > 4.10). Hemoglobin-δ (but not the other subunits) showed a high ratio (M/S = 33.12) in melasma, and, in addition to oxygen transport, its non-erythrocytic expression occurs in situations of cell stress.7 Likewise, up-regulation of alpha 1-antitrypsin (SERPINA1) and actin gamma-1 (ACTG1) is also seen in tissue stress conditions.8,9 The higher expressions of HBD, ACTG1, SERPINA1, and KRT1 in melasma may be due to oxidative stress sustained by mast cell tryptase activity and the secretory phenotype of upper dermis fibroblasts.3,6

Carbonic anhydrase (CA1) acidifies the extracellular environment of the dermis, favoring the repair process, being down-regulated (M/S < 0.33) in melasma.10 The senescence of dermal fibroblasts, associated with the activity of MMP1 and MMP9, promotes a pro-inflammatory microenvironment with degradation of the extracellular matrix and the basement membrane zone, the repair deficit of which may be a factor in the maintenance of melanogenesis.1,6

Androglobin (ADGB) has a cysteine-endopeptidase regulatory function, being identified in a lower ratio (M/S < 0.33) in melasma. Endopeptidases participate in the degradation of melanosomes in the epidermis, notably reduced in melasma.

The alpha-kinase anchor proteins (ANCHOR9, ANCHOR13) and the z-catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase (REV3L) showed an imbalance in the skin with melasma. They are important in the regulation of protein kinase-A and the p38-MAP kinase pathway, involved in the activation of the CREB protein, which leads to the expression of MTIF, a promoter of melanogenesis.3

Aldolase-A (ALDOA) has a glycolytic function and is associated with the activity of mast cells, which, in the superficial dermis, promote changes in the basement membrane, solar elastosis, and endothelial dilation, reinforcing the idea that stimuli originating in the dermis play a central role in the melanogenesis of melasma.2,3

Fibrinogen-γ (FFG) is an extracellular matrix protein, and interacts in several biological functions, including fibrinolysis, fibrinogen activation and activation of the ERK pathway, a promoter of melanogenesis.

The main limitations of the study are related to transmembrane, serum and lipid-conjugated proteins, which are not identified by the method. However, it consistently points to a number of proteins with a pathophysiological role and potential therapeutic manipulation of which should be explored in specific assays.

In conclusion, the study identified 29 differentially regulated proteins in melasma, involved in energy metabolism, cell transport phenomena, regulation of melanogenesis pathways, hemostasis/coagulation, repair/healing, and response to oxidative stress. This supports the research of therapeutic strategies aimed at the identified proteins and their functions and shows that melasma does not depend exclusively on the hyperfunction of melanocytes but also on functional alterations involving the epidermal melanin unit, basement membrane zone and upper dermis.

Financial supportFUNADERSP (048/2016).

Authors’ contributionsLuiza Vasconcelos Schaefer: Design and planning of the study; drafting and editing of the manuscript; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; intellectual participation in the propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of the studied cases; critical review of the literature.

Leticia Gomes de Pontes: Collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Nayara Rodrigues Vieira Cavassan: Collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Lucilene Delazari dos Santos: Critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Hélio Amante Miot: Critical review of the literature; critical review of the manuscript; statistical analysis; approval of the final version of the manuscript; design and planning of the study.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Study conducted at the Department of Dermatology and Radiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, SP, Brazil and Centro de Estudos de Venenos e Animais Peçonhentos, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu, SP, Brazil.