Dear Editor,

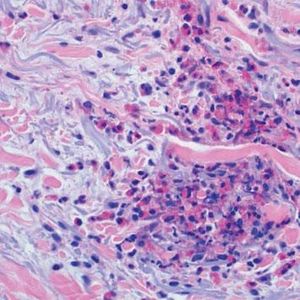

We describe three female patients with recurrent episodes of skin lesions that were diagnosed with Wells' syndrome (WS). The first case we report is a 37-year-old female patient that has presented with red, infiltrated, circular plaques with high and precise borders for the past two years. Some lesions show a central dissected blister, as well as erythematous maculas on the periphery; lesions are asymptomatic and located on the face and upper limbs (Figure 1). The episodes resolved spontaneously in approximately eight weeks and reoccurred, on average, every two months. The second case is a 34-year-old white woman who has shown recurrent erythematous-edematous plaques and papules with central desquamation for the last five years; the lesions first appeared after her first pregnancy. Initially, the lesions were limited to the left forearm, however they later affected the sternal region, being more intense in each crisis. The third case is a 42-year-old white female patient that has presented pruritic erythematous-edematous plaques with papules for 6 months in the cervical region and asymptomatic erythematous maculas on the left shoulder. (Figure 2). Peripheral eosinophilia was only observed in one patient. The anatomopathological findings of the three patients showed eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate compatible with WS (Figure 3). In all three cases, treatment with oral steroids led to the disappearance of the lesions but relapses occurred after the drug was discontinued. Late diagnosis of WS is common, mainly due to the polymorphism of cutaneous lesions and the absence of well-established diagnostic criteria and pathognomonic aspect. Thus, a wide range of differential diagnoses is possible, such as Sweet's syndrome, erythema multiforme, lupus erythematosus, and bacterial cellulitis.1,2 The etiopathogenesis remains unknown but the hypothesis of type IV hypersensitivity reaction, sensitizing T lymphocytes, has been suggested.3 Eosinophil, the main pathophysiological element, is believed to be cytotoxic and protein-secreting of cellular modulators, such as histamine, cationic proteins and free radicals. As a circulating cell, the eosinophil migrates to various tissues through chemotactic stimuli of T lymphocytes, keratinocytes, and mast cells. The involvement of interleukin (IL)-2 in the degranulation of eosinophils in patients with eosinophilia, such as SW, has been suggested. Eosinophils of these patients express the IL-2 receptor α-chain (CD25) and platelet-activating factor, thus IL-2 would stimulate the release of eosinophilic cationic protein from CD 25.2,4 Eosinophils are activated by cytokines of type 2 helper (TH2) cells, which produce IL-4 and IL-5. IL-5 would attract eosinophils and regulate their adhesion molecules. CD4 + and CD7- circulating cells in patients with WS participate in the production of IL-5. An increase in the ratio of CD3 + and CD4 + suggests that activation of T cells is involved in the pathogenesis of WS. Systemic involvement is rare, but fever, malaise, and arthralgia are described. Clinically, the initial symptoms of the disease include ardent prodromes, mild pruritus, and the presence of well-defined annular or arcuate plaques, sometimes with a violet halo, erythematous nodules, infiltrates, vesicles, hemorrhagic blisters or hives. These lesions evolve rapidly during the first 2 - 3 days and then shrink, reducing the edema to a brownish-gray, residual, transient, sclerodermiform hyperpigmentation. The spontaneous resolution occurs in 4 to 8 weeks.1,2 The predominant topographies are the lower limbs, followed by the upper limbs, trunk, face and neck.3 In terms of histopathology, three stages are recognized. At first, there is dense dermal infiltrate, rich in eosinophils and extending up to the subcutaneous tissue. The second stage is characterized by the appearance of flame figures, which consist of a dense aggregate of adherent eosinophilic grains surrounding the collagen.5 In the last stage, the flame figures are surrounded by histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a foreign body reaction arranged in palisade.5 Although the flame figures are characteristic of WS, they are not pathognomonic as they may be present in insect bites, pemphigoid, mastocytoma, dermatophytosis, scabies, scurvy, and eczemas.1,2 The therapy of choice is oral corticosteroid.2 In cases where the drug is contraindicated or in cases of therapeutic failure, other options have been described, such as dapsone, minocycline, tetracycline, antihistamines, griseofulvin, azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and anakinra.2 WS seems to be a reactional cutaneous state to several stimuli, thus requiring research. Drug management is indicated, although spontaneous resolution of the condition may occur.